ann y.k. choi

Toronto-based author and educator

All Things Under the Moon

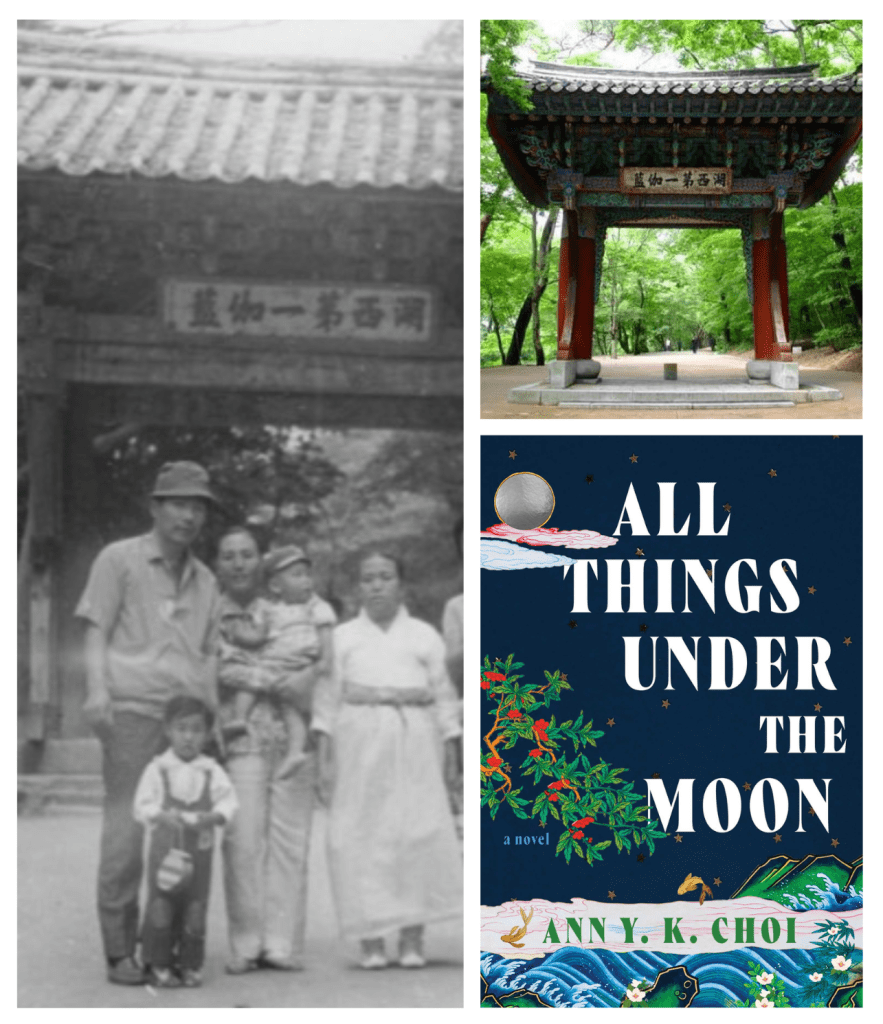

Far left: My father, mother, brother Dong-Ho, my great-grandmother, and me at the entrance gate of Beopjusa Temple in Boeun-gun, Chungcheongbuk-do, South Korea, 1972

Top right: Beopjusa Temple, present day. Photo source: Korea Tourism Organization

Beopjusa Temple was built in 553 during the 14th year of Silla King Jinheung’s reign. Most of the original buildings were destroyed during the Imjin War of 1592-1598 and rebuilt in 1624. Learn more about Beopjusa Temple.

Inspiration

I immigrated to Toronto, Canada in 1975. I was seven years old.

When my daughter majored in East Asian Studies at the University of Toronto, I was exposed to Korean Studies for the first time at the age of 49. All throughout her four years of undergraduate, I read every article and textbook she read and got a crash course on Korean, Chinese, and Japanese history.

I was most interested in the years that my harmony, my great-grandmother, was a young woman, the 1920s. She was an incredible storyteller! I learned as an adult the reason why my great-grandmother never read to me. She was illiterate. Did my great-grandmother ever want to know how to read and write? As bizarre as it sounds, I wanted to gift her that, especially after hearing about how heartbroken she had been when her husband took a second wife – which was allowed if a man could afford to do so. And so, this novel is a reimagining of her story, inspired by a core message that runs throughout the story: women need other women to survive.

Resources and Making Connections

I want to share some of the books, articles, and other resources that helped inform my new novel. It’s my opinion that readers would benefit from exploring the impact of Korea under Japanese colonialism, which ended with Japan’s defeat in World War II, to better grasp the impact that that period continues to have on present-day Korea.

These historical materials hold the key to understanding a large part about colonial practices and the consequences for those oppressed for decades after. While modern-day Canadians may feel distant from fears of colonialism, we need only look a few paces behind us to see the impact it had in our own country. Canada’s Indigenous Peoples are still reeling from the effects of the suppression of their culture, language, and identity, even amidst reconciliation attempts by the Canadian government. In many ways, looking to understand what happened to people across an ocean can help us better understand what happened to the people whose footsteps we stand in now.

Key locations

Tapgol Park in Seoul. On March 1, 1919, thousands of Koreans gathered in this park calling for Korean independence. Top right and bottom right: traditional rooms with bedding on the floor (nights) or folded away (day). Photo credit: C Choi McCanny

Even most Koreans have never heard of Daegeori, the tiny village where my great-grandmother lived. I called her Daegeori-harmony. It was common practice to add one’s place of residence so that we could tell our many great-grandmothers and grandmother apart. My grandmother from Anyang, my mother’s mother, was Anyang harmony.

In my desire to recreate my protagonist’s world as authentically as possible, my daughter and I travelled to each location mentioned in this novel, from Seodaemun Prison where sixteen-year-old Yu Gwan-Sun was tortured and killed for being a freedom fighter, to my great-grandmother’s old home, and to the mountains of the tiny village not found on any map that serve as formidable bookends of this novel.

Key ideas and concepts

Growing up, Buddhism was a way of life more than a religion. Above: my family's temple in Toronto, Canada.

My great-grandmother was a vivid storyteller. The first time I’d ever heard of the rabbit and turtle tale was not about a race, but rather a turtle tasked with cutting out a rabbit’s liver so that it could be used as healing medicine for the Dragon King who lived under the Southern Sea. Each of the stories I heard unconsciously taught me Korean culture, customs, and traditions. They stayed with me long after I left the country and shaped parts of my identity and core values.